By Rea Scovill, Ph.D.

Fight-or-flight responses are reactions to danger, particularly life-threatening danger. They include: for fight, angry speech and physical or written confrontation; for flight, leaving the situation physically or through mental distancing and other forms of avoidance. They originated in early stages of human development, when life-and-death situations were frequent. At some point our fight-or-flight responses expanded from situations where our life’s at stake to situations where we just feel stressed.

This means that today, when our lives are rarely threatened, disturbing fight-or-flight impulses can occur many times a day. When we lose our keys, feel upset with another person or worry about something, our bodies may be triggered into action. A tense jaw or fist, upset stomach and racing thoughts offer nothing useful to cope with these events. In fact they interfere. For mental fitness, or even mental health, we must clearly grasp this fact.

Once we do grasp it, our brain will struggle to remember it from moment-to-moment. We may detect inner chatter that insists we can’t stand it when we lose our keys, etc. When upset with other people we might say we must have another person’s approval, or someone really deserves to be punished, or it’s unbearable when we don’t get rewarded for working hard. These extreme inner comments often trigger our fight-or-flight response. We need to learn how to stop all this by saying something like, “chill now, this is not about life or death, it’s just disappointing, annoying, hurtful, etc.” That would be the truth, and that would open us to the freedom of mental fitness. This seems so simple; why do we find it so hard?

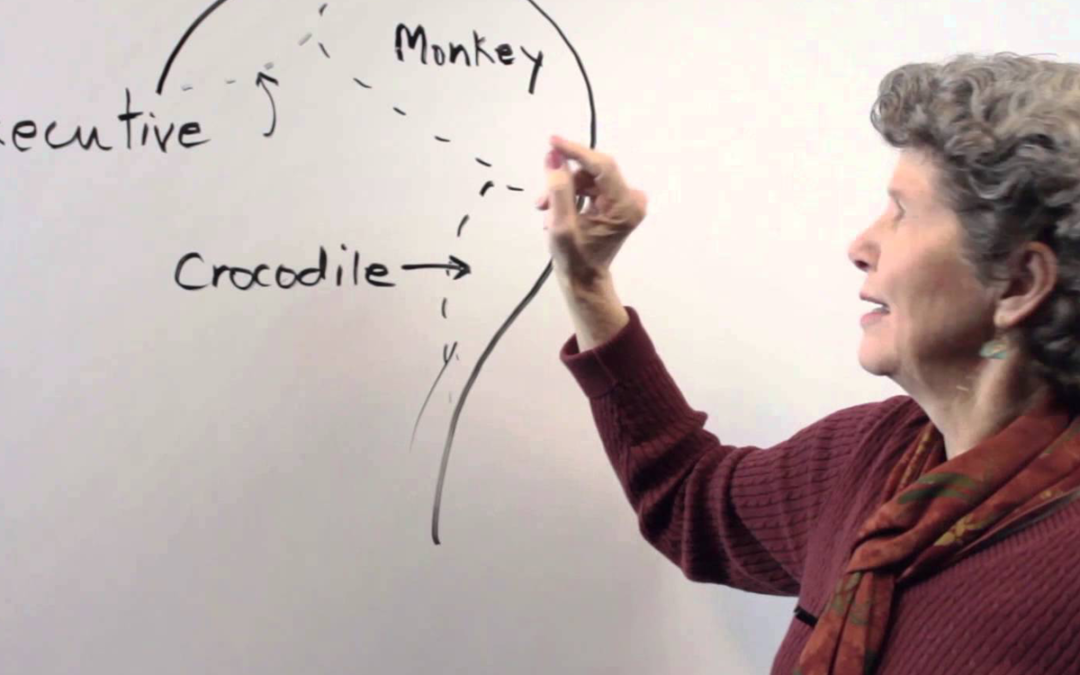

For mental fitness you don’t need to learn the names of specific brain parts, though the brain is very interesting. You do need enough understanding to prevent frequent disruptive over-reactions. Here’s what you need to know about your brain to start. The first brain area is the frontal lobe, often called the Executive Brain. It functions as the director and manager of your being. It chose to read this article. It’s also supposed to advise the rest of your brain when fight-or-flight isn’t needed.

However, your Executive Brain can’t do this when it’s overwhelmed by your other brain parts. I call the second part the Monkey Brain because it’s similar to other mammal’s brains. It receives, processes and stores data from your senses and your Executive Brain. Its focus is to identify anything that it considers dangerous enough to require a fight-or-flight response. Once something appears threatening, it signals the third part, that I call the Crocodile brain, because it’s similar to a reptile’s brain. As it’s signaled, the Crocodile brain begins to trigger your body into action.

Your Executive Brain has to interrupt your Monkey Brain with reality checks all day long every day. Otherwise you’ll find yourself in one stage or another of fight-or-flight too often. Our next article will describe how 15-20% of us are wired to have these reactions more often and with more intensity than the rest of us. Our Executive Brain must take brain differences into account before we can relate to others with fairness and compassion.